The Center for Interfaith Relations is exploring the written works of theologians, poets and other wisdom-keepers in search of insight and inspiration. Our hope is that these written words will spur meaningful reflection and serve as a beacon of hope amid challenging times.

So What Is Hope?

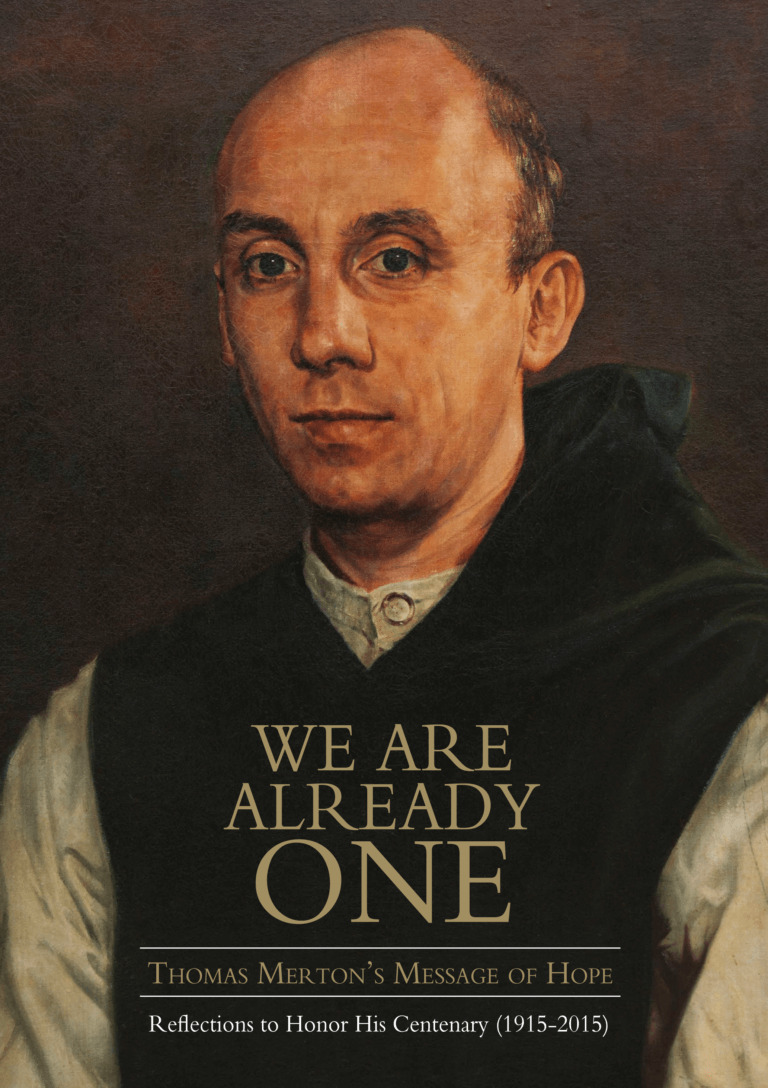

By Anthony T Padovano | From the Collection “We Are Already One“

Hope has a way of being elusive and imperative. Because it is elusive, we wonder at times if hope drifts into fantasy, an evasion of reality. Hope’s elusiveness makes it difficult to measure it, at times even to engage it. Because it is imperative, it summons us regularly and emerges relentlessly from all the ways we seek to banish it.

Hope may be elusive, but it is woven into the fabric of everyday life. We can’t walk or speak without hope. Despair leads us to immobility and incommunicativeness. Albert Camus, an alleged non-believer, noted that even to take breakfast is an act of hope. He was not speaking theoretically when he said this. Perhaps the only way to reflect critically on hope is to consider what happens when it is gone.

Human truth is not fully defined by cognition and reason, by logic and clarity. The truth of something is also validated by the effect it has on our life and on the lives of others. The measure of the damage the absence of something causes is reason enough to justify its presence and validate its necessity.

The World a Sacrament of Hope

It is facile and reductive for believers to dismiss the so-called secular as unreliable relativity. There are no secular realities. Christians should have known this all along, even more clearly than others. If grace is everywhere, it has no boundaries. Like love, it finds its way to all of us.

There are many signs of grace and hope along the secular paths of history. In the last century, we have experienced the lowest levels of violence since the paleolithic age. Harvard professor Steven Pinker has traced the statistics of this phenomenon in his book, The Better Angels of Our Nature. Those of us that only see the horror that tragically broke our hearts in the last century are those who read history less deeply. Sometimes this selective reading of history happens because people assume, cynically, that there is depth in negativity and hopelessness.

The last century expanded rights and justice for women and minorities, for homosexuals and dissenters on a scale unimaginable just a few years previous. We may get a measure of the enormous progress by imagining ourselves living in 1900, shorn of all the human development that followed. Women could not vote and homosexuals had no rights. There was no ecumenical movement, and interreligious dialogue was non-existent. Higher education and regular health care were simply out of reach for almost everyone. Retirement was not a possibility, and travel, before airplanes, was circumscribed. The European Union did not exist, and, in the United Sates, segregation was enforced and the idea of an African-American president was exotic. Women priests or bishops, women Supreme Court justices, or Secretaries of State, indeed, President or Speaker of the House, were the stuff of fantasy. The list could be continued but the point is made.

The Soviet Union collapsed and the Third Reich was destroyed. Some of humanity’s worst diseases were eliminated. The population of the world reached seven billion and every day the vast majority of this number are fed and sheltered. The large number still malnourished is sad beyond all description, but we must not take for granted the billions who survive or even thrive.

I hope, therefore, because I experience the world as a sacrament of hope. I do this, at times, when I find the Church is not. I become more confident when the Church joins the world and the best moments of each converge. The church achieved this in the Second Vatican Council. The magnitude of that Council is all the more evident when one compares its immediate predecessors Vatican I and Trent. Catholics experienced the world before Vatican II as one in which attendance at Protestant services was grievously sinful and the slightest sexual deviation merited eternal damnation. The mass was in a language almost no one understood. And laity were banished from proximity to its celebration in all but minor ways. Indeed, the laity accepted its distance from Church life and leadership as proper,. The New Testament was not a book Catholic leaders urged people to read on their own or to interpret critically.

The Church, as a sacrament of hope, united to a world as a sacrament of grace, enable me to see my own life and the lives of my contemporaries as sacraments of hope. It would be dreadfully naïve and inexcusably obtuse to disregard the effects of evil and sin, to make light of the unbearable suffering we inflict on one another and the damage we do by our arrogance and predatory exploitation, our greed and narcissism. The catalog of theses aberrations and deviations, the prevalence of dysfunctionality and will diminishment of the other, the bigotry and torture, war and homicide, sexual abuse and financial corruption, this catalog is well-documented and graphically inescapable. My intent is not to add to this, since it is well-known and obvious. My intent is to draw attention to the sacramentality of human existence in all its many forms and its awesome capacity to receive and incarnationalize grace. Humanity is not primarily defined by its lapses.

I find great comfort in the spiritual lessons that so-called pagan and classical literature give us. Cicero’s essays on friendship and aging, Aristotle’s ethics and Plato’s Republic show the human spirit, before Christianity, as capable of impressive spiritual depth. Homer’s Odyssey gives us the choice by Odysseus to leave the island of a goddess even though she offers him endless sexual pleasure and everlasting life because he does not love her and wants to be with his wife Penelope and his son Telemachus. Homer reminds us that there is no greater happiness than a marriage built on love.

Virgil, in the Aeneid, begins with Aeneas running from the destruction and flames of his native city, Troy, with his aged father on his shoulders, his young son at his side and his household gods in his arms. The symbol is unforgettable. It tells us that when our lives are in ashes, we gain hope again if we preserve our memories (his aged father), our hopes for the future (his young son), and our values (the household gods).

Merton as Mentor

When Dante journeyed to the Inferno, he had Virgil as a guide. When he ascended to Paradise, it was Beatrice who led him there. He did not encounter darkness or the light without mentors.

The spiritual life is a journey that takes us through the dark corners of our life in the truth and the love which give us peace and bring us hope. We seek guides for such a journey, people who reassure us that the journey is not a phantom venture, that, indeed there is more to life than the few decades we have from birth to death. Even more to the point is the character of the life we have while we have it. How do we find God, and how do we deal with one another? Does prayer reach God and does it benefit others? What is our responsibility toward the poverty and pain of people? What do I do with the envy in my life, or the greed, with the arrogance and narcissism, with the fears that God may not exist or that others are not worth my effort, with the enemies I make and my ingratitude to those who love me?

Thomas Merton encapsulated this message in his life. There were paradoxes. He embodied what he wanted to say in the silence he chose. He became a prophetic witness for social justice in seclusion. He changed the lives of others by what he experienced in in contemplation. He made us hopeful by the simplicity of his life, a simplicity which convinced us that we could not follow such a path, not in monastic confinement only, but in the seemingly ordinary journeys of our lives. We could all readily be silent and allow more time for seclusion and contemplation.

Clearly, one of Merton’s great books, a spiritual classic, Seeds of Contemplation, made mysticism not an exotic calling, but a vocation to which we are all summoned. He showed us that the arc of our individual lives is not limited to the emergence of consciousness and intelligence, reason and conscience, morality and compassion. All of us take this journey and know that human development requires these steps. We readily conclude that those who reject this path are humanly underdeveloped.

Merton, however, insisted we are capable of more. There are mystic moments in all our lives. Those instances when we are willing to give ourselves totally to something larger than ourselves. We do this in love when we willingly lay down our lives for others. We do this with our deepest commitments which carry fidelity with them, to a life partner or a friend, to children or to country, to universal peace and non-violence, to social justice for the oppressed. At the heart of our relationship is the yearning to encounter beauty. It is mysticism which forms the soul of the artist and creates the voice of the prophet. We reach for God and experience God as the source of the mystery and mysticism in our lives.

Mysticism is the experience we undergo when we see that all the opposites are at one with their alternatives. We behold the universe as a harmony, and discern that the discordant notes blend and that we are one with the universe in its great symphony. We touch mysticism when we fall in love and when the joy and exhilaration of it makes us want this for everyone. At such moments, we have no enemies and choose to have no one excluded. Mysticism brings our lives into wholeness.

Merton crafted in his silence the words to assure us of this. He did this in the singularity of his own Cistercian, by writing, not so much about monasticism, but about us. He stated that monasticism is validated if it brings with it not only an encounter with God, but a connection with all humanity.

Merton gave us hope and became our mentor by assuring us that our lives were exalted and that there really were no hierarchies separating the ordinary from the special, the everyday from the exceptional.

Life itself, humanity lived, is the great sacrament. Like all sacraments, it is the visible expression of a reality inexhaustibly sacred.

Hope and mysticism belong together, each of them not justified by logic, not requiring evidence, not able to be done away with, without discarding human life itself. We are mystically called to love a life of hope even though the arguments contrary to hope seem more logical and rationally more compelling. There is no way to justify with logic alone the power of love or our universal vulnerability before it. Love is mysticism’s finest moment and it leaves hope in its wake.

Merton led us in these directions and invited us to become pilgrims with him. He called us as a brother and made us feel that someone in our own family, someone who knew us well and cared for us, someone able to find the words we needed most to hear, was addressing us. This was Merton’s great genius to reveal to us in his life and writing how to find hope in who we are and how to become mystically one with those larger realities which bring us peace and make us feel at home. Merton’s own life was not easy, nor is ours. Love is not an easy commitment. It costs not less than everything. But it gives us, in return, ecstasy and happiness and freedom and peace. In a word, it gives us hope.